|

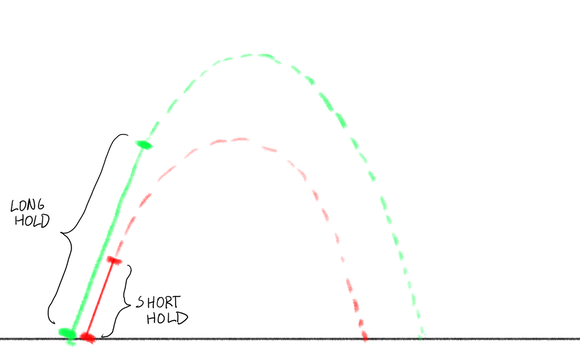

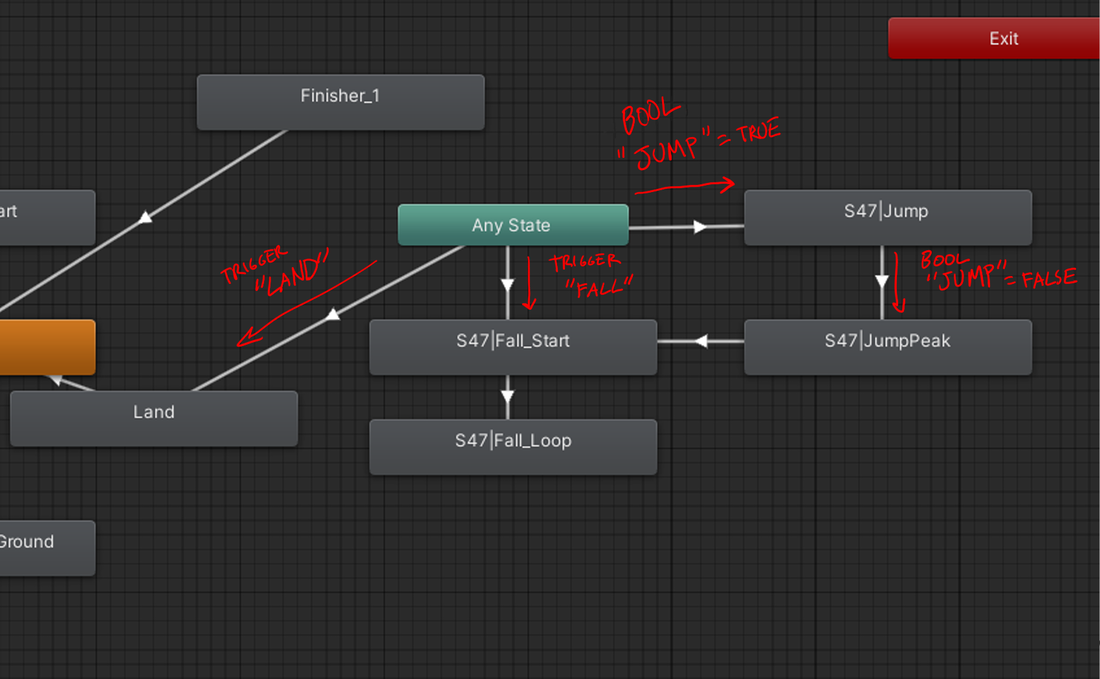

I've been working on a third-person game lately (check out @catbirdsoft on twitter, cohost, bluesky, whatever) and that's meant that I've been solving some problems that I was mostly able to ignore while working on my FPS projects. The most recent of those problems that I've had to deal with is animating a jumping character, and I had to do a bit of trial and error on my own to come up with a satisfactory solution. Here's that solution in blog post form, in the hopes that it'll help some other people who are trying to do the same thing. Jump animations are something that can mostly be ignored in first-person games, because the first-person character is an invisible capsule and players mostly expect it to move like one. In third person games, however, you gotta actually make the character move in a way that feels both responsive and fluid. There are plenty of excellent tutorials for making jump animations online, and if you follow them you might end up with a cool jump animation like this: The problem with this animation, though, is that it only works on flat ground. Fighting games can get away with this because their stages are flat and empty, but most games will feature some terrain variation. Because of this, we have no way of predicting how long the character's jump will last and where they will land. This means we don't need a single jump animation, we need a set of animations that combine to form every possible jump. Now that we know that, we can start breaking down our jump animation into game-ready pieces. There are five key movements in a jump. Let's look at each of these movements and see how they might vary in-game. Movement 1 is an anticipation pose. The character squats, gathers power, and prepares to launch off the ground. Many game jumps eliminate this pose to increase responsiveness - spending frames on anticipation means a noticeable delay between pressing the jump button and leaving the ground, which can make controls feel sluggish and frustrating. Movement 2 is an extension pose. The character has sprung off the ground and is rapidly moving upward. This pose should be held for as long as the character is actively launching themselves into the air. In most games, this will be a constant period of time. In Movement 3, the jump peaks. The character brings their arms down while inertia carries their legs up, then begins to fall back to earth. The length of this peak is determined by your character's initial velocity and their gravity acceleration. In Movement 4, the character has extended again. Their arms trail behind them. This time they will spend in this pose is highly variable - after all, we have no way of knowing how far a character will fall when they start a jump! Movement 5 happens after the character touches the ground. This is a recovery pose, as the force of the impact carries through the character's body. While this may look similar to pose 1, it's much safer to keep! You can move the character during this recovery pose, or cancel it with another action. You might want to vary this depending on the height of the jump, but a fixed animation will work just fine. So, how should we take these movements and convert them into animation clips? First, decide whether or not you want to include anticipation frames before the jump itself. While this will make the jump less responsive, it will make it look better, and a little delay on a jump can be great for action games that don't want players to be able to instantly jump out of the way of attacks (fighting games in particular use this to ensure players don't spend the whole game hopping around the screen). If you choose to include an anticipation period for your jump, I would recommend making it a separate animation clip. This will let you adjust its speed independently of the rest of the jump, and make cutting it easy if you decide it messes with the flow of the game. Alternatively, you can limit the anticipation pose to the very first frame of your jump - this will cause a more dramatic "snap" to your extension pose, making the jump appear more energetic. Next, look at your jump arc. While some characters will have a perfectly parabolic jump arc (an initial velocity set on the first frame of the jump followed by a constant downward acceleration), platformer developers may wish to alter their character's movement in physically inaccurate ways. A common trick you might want to use is a "hold jump" - to enable finer movement control, the player can hold down the jump button to extend the character's launch period, causing them to jump higher. In the above image, we can see the effects of the hold jump on the character's trajectory. While the jump is being held, the character's upward velocity remains constant. After the hold is finished, the character resumes their parabolic trajectory. The period that we are stretching along with the hold is the extension pose. If you have a jump like this in your game, Movement 2 should be its own animation clip, and you should transition out of it once your hold period is complete. For my project, I chose to combine Movements 1 and 2 into a single clip (played above at 25% speed so you can actually see it). It's a very quick transition from a crouched anticipation pose to an extension pose. Once in the extension pose, the clip ends - we're fine with holding on the last frame until it's time to transition to movement 3. Now that we're out of our launch period, we have to handle the peak of our jump. In this case, we'll want a single clip that brings us from Movement 2, past Movement 3, and towards Movement 4. All of these movements happen on a fixed timeline, so we don't need to break them up. You can do some simple math to figure out how long this peak animation should last: if Vi is your initial velocity after launch, T is time in seconds, and G is your gravity acceleration per second, then you should hit your keyframe for Movement 3 when Vi - (T * G) = 0, which is Vi / G seconds. Or, if math is hard and you don't want to do it, just animate the thing and then speed it up or slow it down in-engine as needed. One upside of splitting our jump into clips like this is we can just dial individual parts of our jump in after animating them! Despite saying we could do this section in one clip, I included a split here for one reason: I want to be able to smoothly transition into Movement 4 when the player walks off the ledge. Movement 4 is a generic "falling" animation, so I can reuse it for non-jump aerial movement. Shown here are two clips: one "jump peak" animation, and one "fall start" animation. When we jump, we transition automatically from the jump peak to the fall start as if they were one clip, but when we start any other aerial movement we transition straight to the "fall start" animation. (If this is confusing you, don't worry - I'll also include a screengrab of the animation graph at the end of this post). As you can see, the "fall start" animation looks pretty bad by itself - it's a single transition that only works as part of a bigger animation. Once we've finished the fall start animation, we're all the way into Movement 4, but we still don't know if we've touched the ground! In fact, if we're falling a long distance, we might have to hold our Movement 4 pose for several seconds or more. That's why we're adding yet another clip to our jump - a looping fall pose with a little secondary movement. This also doesn't have to look great, unless you're planning on making long falls a common part of your game. We hold this clip until we make contact with the ground, at which point we play a little landing animation (Movement 5, our recovery clip). Once again, this is a pretty quick and simple animation - I even sped it up after putting it in engine. We just want to show the character in their impact pose briefly, then bring them back to a standing pose so they can run around on the ground like normal. You'll also notice that we start in the impact pose rather than transitioning from the fall pose. The fall to land transition happens in the blend between the fall clip and the land clip. Because we want the impact to be sharp, the transition only lasts for a frame or two. Here's what the jump animations look like laid out inside a Unity animator. We have one boolean and two triggers that govern our jump - "Jump," a bool which starts the jump process, "Fall," a trigger which starts the fall process, and "Land," a trigger which terminates the jump. Setting "Jump" to true moves us to movement 1, where we then hang until it is set back to false. Afterwards, the animation automatically progresses along the movements we described until it gets to the Fall Loop clip. It can be interrupted at any time by landing, because (as mentioned above) we have no idea when we're going to hit the ground. If the player falls instead of jumping, the "Fall" trigger smoothly transitions us to Movement 4. Now that the animations are in-engine, let's see how they look when they're put together: Boom! The animations flow together smoothly. It's unlikely that players will notice all the effort spent on this jump once the game ships, but they'll be jumping often enough that I feel it is worth the time investment (although I haven't even got to the VFX... that's an ordeal for another blog post).

I hope this was helpful! If you found something in this post unclear or confusing, please let me know in the comments or via email or whatever and I'll do my best to clear it up. If you have questions about the code used to trigger these animations, feel free to ask about that, but it's basically separate from the animation work itself so I've chosen not to discuss it in the post itself.

0 Comments

Spoiler Warning: This article contains late-game footage from Wo Long: Fallen Dynasty and Elden Ring. I: Wo LongRecently, I’ve been playing through Wo Long: Fallen Dynasty, a Soulslike by Team Ninja, the creators of the Nioh series. It retains Nioh’s over-the-top combat design, but this time with a heavy dash of Sekiro’s high-speed swordplay - including a viscerally satisfying deflect system that takes Sekiro’s parries and gives them an aggressive twist. It’s easy to understand, but also satisfying to master. That said, its combat system has some limitations that neither of its primary influences do, and I think we can learn a lot about combat design from how those limitations make themselves known in the game’s enemy and boss design. In Wo Long, you have several defensive mechanics available to you at all times. You can block attacks, you can jump over them, and you can dodge them. However, none of these are as useful as the game’s signature move: deflecting. Deflecting is a half-dodge-half-parry attack that plays into the game’s main resource system: it costs you a little bit of qi to use, but if you land it successfully you earn that qi back and more, and your opponent loses qi instead. A string of successful deflects will put your opponent on the back foot, and give you the resources to launch powerful attacks or spells at them. It’s an intuitive system, and the way it lets you turn your defense into offense feels great in action. Despite my praise for it, though, the deflect mechanic has some negative effects on the rest of the game. Deflecting is the only optimal mechanic to use. Blocking an attack may be easier, but its resource balance is the reverse of the deflect: the blocker loses qi, and the attacker gains it. Jumping or dodging attacks may be situationally easier, but once again, this allows momentum to shift in the attacker’s favor. To top this off, every enemy has powerful “Critical Attacks” at their disposal, which cannot be blocked but grant the defender a massive qi advantage if deflected. The game wants you to deflect at all times, and it makes this clear at every opportunity. While deflecting may move the player like they are dodging, its core defensive properties are most similar to a parry. What that means is that a successful deflect depends entirely on timing, and not on the movement direction of the deflect. You can deflect into an attack, away from it, or any direction you like, and it will be just as effective. There are some caveats to this - you get a slightly bigger timing window when deflecting towards an attack (as your character is more likely to intersect its hitbox), and some critical attacks can only be deflected at point-blank range. That’s not a lot, though, and in the average combat encounter you will find yourself mostly focused on timing your deflects, with positioning relative to the enemy being an afterthought. The result of this is that bosses and enemies have attack animations that are designed around ambiguous timing. Delayed attacks are nothing new to Soulslikes as a whole, but Wo Long takes them to the next level - late game bosses hold their startup poses for ridiculous lengths in order to mess up the player’s sense of rhythm. This doesn’t make the game unfair, although it looks very silly. Rather, it’s necessary, because if these enemies moved in a reasonable way, it would be incredibly easy to deflect all of their attack sequences. Deflecting is so easy, and so rewarding, that it warps the enemies’ movesets in a visible way. Sekiro, one of Wo Long’s most visible influences, also features a powerful parry mechanic that drains the opponent’s primary resource meter. Why, then, do Sekiro’s bosses move more naturally than Wo Long’s? It is because Sekiro’s most dangerous attacks (called “perilous attacks”) cannot be parried. In fighting games, there is a concept called the “mental stack.” A player’s mental stack is all of the things they are thinking about the opponent doing at a given time. Much like a stack of papers, the more items in your mental stack, the longer it takes to find the one you need. If the opponent always approaches you by dashing straight in and attacking, it’s trivial to wait for them to move and counter their dash with an attack of your own. If instead they mix their approach up with jumps and long-range attacks, it’s much harder to react to their dashes. Sekiro’s mental stack is large. The player must react to regular attacks by parrying, and then avoid perilous attacks by either dodging or jumping. Because of that, the timing of each individual attack can be much easier for a player to react to. Their reactions will naturally be slower due to the decisions they have to make each time an enemy’s animation starts up. There are other ways to pile items onto a player’s mental stack. Nioh 2, Wo Long’s most direct ancestor, adds to the stack by giving the player options. Nioh 2’s weapons have gigantic movesets spread across three different stances that the player must switch between during combat. Each stance provides different offensive and defensive capabilities, and mastering all of them is a major part of the game’s skill curve. In addition to this, Nioh 2 places extra pressure on the player’s mental stack at the end of their combo with its “ki pulse” mechanic (to be clear, Nioh’s “ki” is a separate concept from Wo Long’s “qi”, although both represent twists on the usual Soulslike stamina bar). Attacking in the Nioh games costs players ki, but there is a small window after the end of every combo where the ki pulse button can be pressed to instantly recover all of the ki spent in that combo. Like active reloading in the Gears of War series, this requires players to pay attention to the timing of their button press so that they can regain as much ki as possible - an early ki pulse will give you less ki back than you’d like, and a late one will give you none at all. Of course, enemies will be most likely to attack the player in the period after they are done with a combo, forcing the player to both evaluate what their opponents are doing and when they should be ki pulsing. Wo Long’s player-sided combat mechanics are much simpler (there are no stances, no explicit combo chains, and a weapon’s special moves are limited to a pair of “martial arts” attacks). This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but it does mean that the player’s decision tree while attacking is much easier to navigate than in the Nioh series. Also, the way Wo Long’s basic attack and defense moves feed into the qi system is the reverse of Nioh - a successful deflect or light attack causes the player to gain qi. When the player’s qi is low, the risk-reward of combat pushes them to rely on light attacks and deflects, rather than making more complex decisions. Wo Long’s strange boss animations, then, are a result of the game reducing complexity in as many areas as possible. The deflect mechanic has been made the single most important feature of the game’s skill curve, and so late-game challenges must push its limits as far as possible so that the game doesn’t become boring. II: Elden RingElden Ring, another recent game in the Soulslike genre, has also suffered from this problem. Elden Ring is in the unenviable position of not just being a Soulslike, but being the Soulslike - a five-years-in-the-making project from the creators of the original Souls series. As such, it’s stuck with a fanbase that has played a number of Soulslikes before and expects a game that provides familiar mechanics but with fresh challenges. Like Wo Long, Elden Ring’s mental stack is built around a singular mechanic: the dodge roll. Players can technically jump, block, and parry, but (similar to Wo Long) the advantages of dodging are clear and most players will end up ignoring the alternative defensive mechanics in favor of attempting to dodge every attack. Dodging in Elden Ring has more nuance than Wo Long’s deflect - because both attacking and dodging require stamina, players must take care not to overextend themselves. A dodge in Elden Ring also does not interrupt enemy attacks, so players must dodge in a direction appropriate for each attack so that the attack misses them entirely. This gives Elden Ring much more room to build a skill curve. Unfortunately, Elden Ring is also a hundred hours long and the successor to a series of RPGs that also rely on the dodge roll. By Elden Ring’s endgame, players will have learned to simplify the mental process of reacting to an attack even if they have never played a Soulslike before. This is a challenge that the developers were clearly not prepared for. Not only is Elden Ring the longest Fromsoft Soulslike by a significant margin, it’s also unusual in that mechanically it represents the most borrowing From has done between two entries - much of its pacing and combat design is fully carried over from Dark Souls 3. These two factors combine to erase most of the breathing room From had to create easier, more straightforward encounters, and in fact the late-game Elden Ring bosses display their own strange tropes as a result of the game’s enemy design pushing uncomfortably against its skill ceiling. It’s clear that Elden Ring’s developers felt this pressure, and attempted to alleviate it by fleshing out some returning mechanics. The strong attack button was essentially useless in the main Souls series - on most weapons, it was far too slow to justify the additional damage that it could do. Elden Ring’s addition of the invisible “posture” meter for enemies gives stronger attacks additional utility: hitting enemies with a higher caliber of attack will drain their posture faster, and fully draining an enemy’s posture will stagger them and leave them vulnerable to a critical hit. This mechanic is limited, however, by its invisibility and by the way bosses will sometimes ignore it. Since you can’t see an enemy’s remaining posture, it is very difficult to calculate which attack will be most effective to stagger them with. Compounding this difficulty is the fact that bosses will sometimes enter states with infinite posture, where they cannot be staggered and in fact will begin to regenerate the posture damage you have dealt them. In theory, this adds even more to the player’s mental stack - a hypothetical ideal player would track the posture damage dealt to an enemy and estimate the posture regained during an un-staggerable animation - but in practice, players simply end up ignoring the finer points of the system and just following their intuition. If you can’t calculate it reliably, and the stagger will happen at some point anyway, why bother being careful about it? Fromsoft also revised many of the meter-reliant mechanics to encourage players to think about resource management in combat. Dark Souls 3 introduced the FP meter, a non-regenerating mana bar that could be used to cast spells or activate special weapon abilities. In Elden Ring, these spells and abilities have been heavily improved, so most builds now have at least one use for their FP. Despite this, the FP meter fails to meaningfully improve the game’s skill ceiling because it is both universal and non-renewable. FP, as a resource, is treated the same as health. Once spent, FP will not regenerate, unless the player spends a charge from their “Flask of Cerulean Tears.” Since the bar and flask charges don’t reset until the player rests at a bonfire, the player begins every fight with an explicitly finite amount of FP to spend. Because this resource powers all of a player’s most powerful attacks, the game then implicitly encourages the player to spend it only on their best attack. If you have multiple options to spend FP on, unless the ratio of FP spent to damage dealt on them is exactly the same, you will choose the one that gives you the most damage for the least cost, and in Elden Ring this option generally does not vary over the course of an encounter. Once again, this doesn’t place a lot of strain on the player’s decision-making process. If you’re choosing to use meter, you generally have two or fewer options, and after a few encounters it’s not difficult to internalize how you wish to spend FP. Elden Ring’s bosses in the late-game don’t delay all of their attacks in the same absurd way that Wo Long does, but they do share some quirks indicative of the game’s lack of mechanical headroom. They use massive area-of-effect attacks, because an explosion that covers half the battlefield is one of the few types of attacks that dodging will not work against. They tend to have some level of dynamic adjustment to their combo flowcharts - often, they will have attack sequences that can loop back into each other if the player dodges the wrong way. They’re also much more reactive in general, and will often dodge or counter players who attack them outside of predetermined periods of vulnerability. Once again, this is a result of the game’s decision-making process being naturally simple. Because players will intuit their way through the basics of combat, it falls on enemy design to make the decision-making process more complex. Rather than attacking whenever an enemy seems vulnerable, players must learn to discern when the AI may react to an attack and when it cannot. Rather than simply dodging based on the enemy’s animation cues, the player must learn when the AI can choose to extend its attack sequence, and when it cannot. It creates an artificial layer of situational knowledge to supplement the game’s base skill curve. III: What can we learn from this?I don’t want to take too many universal lessons away from this. Soulslikes are a niche genre, and while I think much of this applies more generally to action games and other games of skill, we should consider the following limitations:

That said, I think we can draw the conclusion that, in action games, greater mechanical stresses on a player let us make boss fights that fit into the combat system more intuitively. Slowing the player down by asking them to consider more options reduces stress on enemy and encounter design, and lets us build a sense of mastery over the game itself rather than mastery over a specific fight. |

ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed